23

23Slavery and resistance in Quebec

Credits: Media launching of Fugitives! exhibition at Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec.

It’s surprising that people are still astonished that slavery really existed in Québec and Canada. Contrary to what many historians have claimed over time, the St. Lawrence Valley did not escape this practice that was an integral part of European colonization everywhere in the Americas.

Credits: illustration by ValMo, Le grain de sable. Olivier Le Jeune, premier esclave au Canada. Septentrion. 2019

Historian Marcel Trudel counted 4,185 slaves in the history of Québec, from the arrival of Olivier Le Jeune in Quebec City in 1629, to the official abolition of slavery in the British Empire on August 1, 1834.

However, this figure is inaccurate, partly because Trudel believed that, in the past, all Afro-descendants or Africans had been slaves. Also, because in Québec, the practice disappeared some 30 years before slavery was officially abolished in the British Empire. Another reason why it’s hard to know what the numbers are is because it’s difficult to retrace the trajectory of slaves by means of archival material.

But the number 4,185 is useful in putting their presence into context in an Atlantic World which had absorbed between 12 and 13 million African souls in some 400 years.

Credits : illustration by ValMo, Le grain de sable. Olivier Le Jeune, premier esclave au Canada. Septentrion. 2019

Domestic slavery

In Québec, slavery was domestic in nature, compared with the economic slavery on plantations in the southern United States, Brazil and the West Indies. The reason for this difference was not any moral superiority, but climate, pure and simple. The harsh winters precluded sugar, cotton, coffee or cacao plantations. New France’s economy hinged mainly on the fur trade and was not based on large-scale agriculture.

As of the 1680s, Governor General Brisay de Denonville asked King Louis XIV of France to grant the colony the right to have slaves, which was allowed. However, politics, distance and climate were such that no slaveships discharged their cargo directly in the St. Lawrence Valley. Be that as it may, residents could acquire Black slaves anyway by purchasing them from resellers or ordering them from the Thirteen Colonies, Louisiana or the West Indies. Many of them arrived in the second half of the 18th century with the Loyalists who were fleeing the fledgling republic that would become the United States.

Credits: illustration by Dimani M. Cassendo, UNESCO "Esclavage au Canada" brochure, 2020

Black and indigenous slaves

Of the 4,185 slaves inventoried, 1,443 were Black, and the two-thirds, 2,683 were Indigenous slaves. These members of the First Nations were called "Panis." Many of them came from the Great Lakes area and from today’s American Midwest.

No matter their nation, Indigenous slaves were generally called Panis. The word is a deformation of the term Pawnee, a nation whose people were captured as slaves or bought from a certain time in history. Over the years, the term became generic for enslaved members of the First Nations.

Slaves selling announcements in the newspapers

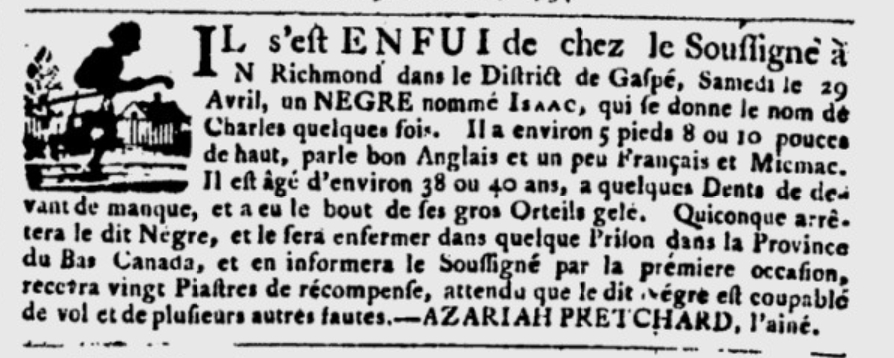

There were no dedicated venues for selling slaves in Québec, but this did not stop the sale of numerous slaves in the marketplace or at auction. As of the time of the British regime and the beginning of the written press with the founding of the Quebec Gazette in 1764, slaves who were for sale were announced in the newspapers, as were fugitive slaves.

Credits: La Gazette de Québec, May 22, 1794.

Because there were no pictures of the slaves of that era, the notices published between 1767 and 1798 provide the most accurate descriptions we have of the appearance of the women and men dehumanized by slavery.

Since the purpose of publishing these announcements was to find the fugitives, the owners described them very precisely, whether it was their clothing and physiognomy or other characteristics, such as marks or scars, hair, the language they spoke, whether they were of mixed identity, or pregnant, all of it in great detail.

The announcements also tell us about the different strategies used by these people to gain their freedom.

Often these wanted notices were followed by warnings to discourage sea captains or others from assisting the runaways.

An exhibition to rehumanize the invisibilized victims of slavery

Credits: Fugitives! exhibition at Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec.

This exhibition enables viewers to visualize the Afro-descendants and Africans who lived in Québec in the latter half of the 18th century based on accurate descriptions.

The purpose is to restore a human dimension to people who were regarded as property to be sold, bought, given, bequeathed, leased or exchanged.

Running away as an act of resistance

Unlike what occurred in the rest of the Americas, where the slave population was much bigger, resistance to slavery in Québec had no choice but to be structured around escape. There were not enough people to mount armed rebellions as was the case everywhere else on the continent.

Hence, the escape of slaves in Québec and Canada is a powerful symbol of agency and of the refusal to accept servility. Women and men resisted using the means they possessed given their feeble demographics. The escape of these slaves must be seen as an act of resistance.

There is very little information about the people who had no rank whatsoever on the social scale, because they were considered property. Furthermore, because the purpose of escape was to avoid capture, two hundred years later it is even more complicated to find them.

As a result, many hypotheses must be advanced in order to better understand the circumstances surrounding their escape and the reasons for it. Even if the domestic character of slavery in the St. Lawrence Valley differed from that of the rest of the Atlantic World and its plantations, it is important to establish parallels because Québec was also part of this colonial universe.

Still a long way to go to include indigenous people

Given the predominant number of Indigenous slaves in Québec (2 to 1 vis-a-vis Afro-descendants), one might be surprised at their great absence from this exhibition. However, the slavery of members of the First Nations occurred mostly during the time of New France, and since this project is based on announcements published in newspapers during the British regime, they are less present.

This exhibition deals with the Afro-descendants and Africans in Québec’s past and their resistance to slavery. Of course, a great deal of research remains to be done to include Indigenous people.

Numbers that hide reality

In all, since the debut of the written press in Québec, there were 43 announcements of sales concerning Afro-descendants and Africans, as well as 51 search notices. However, not all sales or search notices were announced in the newspapers. In both cases, numbers would be higher, especially since the period of New France is not included.

The information in this exhibition was taken from among other sources the Dictionnaire des esclaves et de leurs propriétaires au Canada français by Marcel Trudel, and from Done with Slavery by Frank Mackey (L’esclavage et les Noirs à Montréal in the French version).